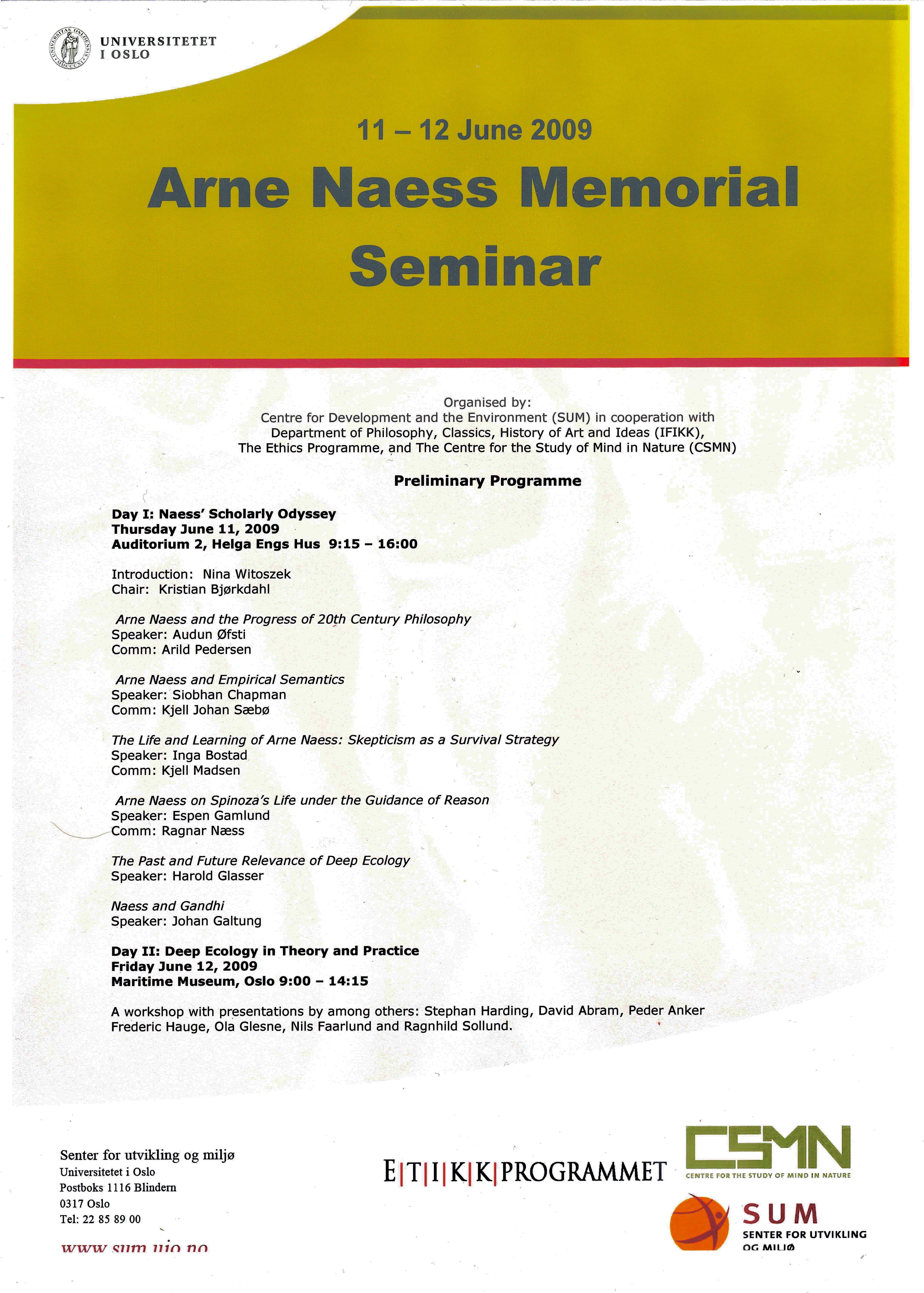

On June 11, 2009, Day I of the Arne Naess Memorial Seminar, I gave a commentary on the paper "Arne Naess and Empirical Semantics" given by Siobhan Chapman. Here is the text on which the commentary was based.

A great thanks to Dr. Chapman for a very insightful and enlightening survey and assessment of that core part of Næss's philosophy, for decades so central to his work and forever so close to his heart, which, in his own words, in the forties got the label Empirical Semantics. What I feel called upon to do is to supply some not actually critical but supplementary comments from a slightly different angle, namely, the perspective of a present-day semanticist in the logical tradition – formal semantics, as it has developed since 1973, the year of publication of Richard Montague's most influential paper.

The Empirical Semantics programme was in large part a critical programme, opposed to major tenets and practices of contemporary mainstream, especially Anglo-American, philosophy of language. I discern two main strands of criticism: the first, the opposition to reducing language to a system of rules, an ideological criticism, the second, the opposition to introspection and intuition – a methodological criticism.

The first stance involved the insistence that language has, essentially, a social dimension; the emphasis on variance and vagueness, and on variance of precision, also called the definiteness of intention; the focus on language in use, the conviction that language use is much more sloppy and diverse than any set of rules could predict. Here, I believe it is clear that time has proven Næss and Empirical Semantics right, specifically through the emergence of novel subdisciplines of the study of linguistic meaning: foremost, pragmatics and sociolinguistics; but also through the large-scale incorporation of various aspects of context and discourse sensitivity into more or less "pure" semantics since the late 1970ies.

The second stance involved the insistence that semantics should be testable and tested, based on a deep distrust of intellectualist, "armchair", introspective method. In this regard, it is much less clear that the recommendations of Empirical Semantics have been taken to heart by semanticists. To a considerable extent, we have disregarded them. My claim is that in so doing, we have missed something, but, all things considered, not all too much. So there is reason both for a guilty and for a clean conscience.

To justify the clean conscience first: There is consensus today that there has been enormous progress made over the last forty years or so, that is, after Empirical Semantics lost its momentum, in semantics, in two inextricably linked dimensions: the descriptive and the theoretical. In part, this owes to the emergence, since 1957, of a science of syntax; in part, it owes to the emergence, since 1973, of a science of natural language semantics. (There were important precursors, of course, contemporary with or prior to Empirical Semantics, but coherent theories with real potential for growth were not yet in place.)

Now the Empirical Semantics insistence on testability and actual testing was sweeping: it compassed all semantic statements, including metastatements. Tarski's (1936) notion of truth, so essential to model theoretic semantics, was a major target of attack for Næss. But what is testable? Hypotheses can be tested, hypotheses about, say, entailment relations or semantic infelicities; descriptive generalisations, like: the word "or" is interpreted in accordance with the truth table of propositional calculus (Næss 1961). But theories are stricto sensu simply not amenable to testing. For them, there are other success criteria, not least elegance. A good analysis has a true ring to it to theorists, and this true tone is remarkably interpersonal. The analysis may have consequences in the form of predictions that were not thought of as it was developed, and so may have to be revised if those predictions are not borne out, but it is partly confirmed by a quality of explanation (which was not considered by Empirical Semantics or more generally at the floruit of Empirical Semantics). In fact, the progress made in semantic theory would not have been possible should the warnings of Empirical Semantics have been fully heeded. It is probably fair to say that Empirical Semantics did not envisage a theory of semantics with explanatory force. The scepticism to anything semantic outside the realm of experiment would seem to leave no room for it. A quote from Russell ("Vagueness", published 1923) may seem curiously apt: "But the sceptical philosophy is so short as to be uninteresting; therefore it is natural for a person who has learnt to philosophise to work out other alternatives, even if there is no very good ground for regarding them as preferable."

Still, in the descriptive dimension where Empirical Semantics was at home, there is also ample reason for a guilty conscience among semanticists. On the one hand, introspection, the semanticist’s own intuition, has remained a viable, respectable, and fruitful method of establishing semantic facts on the basis of data, and intersubjectivity among scholars secures a certain reliability. In this way, a large body of semantic fact has been amassed. On the other hand, this body rests on clay feet, as the selection of data has remained erratic, impressionistic, and small-sampled. Indeed, most examples are constructed. In fact, recent corpus-based studies have shown some widely accepted generalisations to have been misguided by the limited imagination of the generic semanticist. What is more, it has been shown that in some areas, the set of data will be prone to be biased and the facts to be flawed. Although occurrence analyses over large corpora are now fully feasible, they have been slow to penetrate into formal semantics. So there is reason to suspect that many alleged facts are in actual fact of a mythical nature. In other words: Semantics is still far from empirical enough.