Kjell Johan Sæbø who?

I am a semanticist, trying to understand how meanings are made with human language, and to share what understanding I gain in an intelligible way.

But I am something else as well.

On this page, I recount what I am as an academic and otherwise and how this has come to be. There are two sections: Professional Paths and Personal Paths.

Professional Paths

I started my university studies at the University of Oslo in 1974 and finished my Master's degree there in 1978. My subjects were English, German, and mathematics, and German was my major.

Why German? That had nothing to do with the language as such or anything cultural. It so happened that the Danish scholar Cathrine Fabricius-Hansen now taught German linguistics at the University of Oslo. She offered to supervise a Master's thesis project on some, any, topic in theoretical syntax or semantics. This would not have been possible in any other department at the time. I could not decline that.

I was an absolute novice to any school of formal linguistics. Cathrine gave me samples of generative syntax and generative semantics to read, but also texts on this new thing, and it shone through that this new thing was the real thing. So I wrote my Master's thesis in Montague Grammar: Tempus in einer Montague-Grammatik des Deutschen. Per-Kristian Halvorsen, who had just finished his PhD at the University of Texas at Austin, cautioned against the project, but Cathrine was unshaken.

Montague Grammar was quite new to Cathrine too. She was introduced to it by Jens Erik Fenstad, professor of mathematical logic at the University of Oslo, who started a cross-departmental seminar series on natural language in 1976 together with philosophy professor Dagfinn Føllesdal and psychology professor Ragnar Rommetveit. Under varying names (Seminar i lingvistikk, Seminar i datalingvistikk, Seminar i semantikk, Forum for teoretisk lingvistikk), this series had an unbroken history up to 2024.

In summer 1980, Jens Erik organized a workshop over several days in Oslo and Telemark, Models for Natural Languages, where Hans Kamp presented early work on Discourse Representation Theory and Jon Barwise presented his joint work with Robin Cooper on generalized quantifiers and early work on Situation Semantics; other presenters included Emmon Bach, Barbara Partee and Stanley Peters.

Cathrine encouraged me to propose a PhD project and apply for a grant to carry it out. In a late phase of this project, her friend Arnim von Stechow offered me a 9-month research position at the University of Constance, FRG. So in the early morning of Jan 3, 1984, I stepped off the train and found my way through winding alleys to his home at St. Stephansplatz and to his wife Franziska's studio in the same house, where I got a room.

It goes without saying that the University of Constance provided a favorable environment for research in semantics. Also working on their dissertations were Manfred Krifka (who had a 6-month research position) and Ede Zimmermann. Wolfgang Sternefeld (who sublet a room to Manfred Krifka) had just finished his (I hand-wrote the minutes at his rigorosum). Rainer Bäuerle was there, Arnim himself a strong presence. When I left, my dissertation was all but finished; Notwendige Bedingungen im Deutschen: zur Semantik modalisierter Sätze was printed as no. 108 in the series Papiere des SFB 99 in 1985. That is the urtext on what has come to be known as anankastic conditionals.

On January 3, 1987, I stepped off the train in Tübingen to take up work in the project Linguistische und logische Methoden für das maschinelle Verstehen des Deutschen 'Linguistic and logical methods for machine understanding of German', LILOG, sponsored and coordinated by IBM Germany in Stuttgart and involving consortia all over the Federal Republic. My boss here was Franz Guenthner, and Rainer Bäuerle was his deputy. Also in Tübingen were two other Constance companions, Manfred Krifka and Ede Zimmermann.

LILOG was an ambitious project, aiming at a question answering system that could answer any question based on any text that was fed to it. For the first prototype, the text was a hiker's guide to Alsace. (That is where Manfred Krifka's Four thousand ships passed through the lock example came from – see separate story under Miscellanea.)

Over-ambitious. Managerial idealism rubbed against scholarly realism, and more efficient programming languages jarred with beautiful Prolog, so treasured by Professor Guenthner. Our group in Tübingen was an easy target: We were charged with automating text coherence, providing algorithms for still ill-understood phenomena like anaphora of different sorts and types, ellipsis, and discourse particles. Yet it wasn't all frictions and frustrations – for example, one of two LILOG papers accepted for the 1988 COLING conference came from us.

In Oslo, from May 1988, first as a research fellow at the new Institutt for humanistisk informatikk, then as an associate professor of German linguistics, I had the great fortune of collaborating with Professor Fenstad's group of young mathematicians, most closely with Jan Tore Lønning and Helle Frisak Sem. This was the time when the cross-disciplinary programme Språk, logikk og informasjonsteknologi (SLI) came into being, and students in our classes here, notably Bergljot Behrens, Kjetil Strand and Ingebjørg Tonne, also became collaborates. It was a time of high energy and high hopes.

Much of that was channeled into two Ésprit projects we participated in, Dialog and Discourse (DANDI) and Dynamic Interpretation of Natural Language 2 (DYANA-2), and an NOS-H project in the late 1990s, Comparative Semantics for Nordic Languages (NORDSEM), with gratifying returns.

Through my years as associate professor and, from 1996, professor in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Oslo, I have striven to build bridges – between ways of doing linguistics and between places where linguistics is done. I was ideally positioned to do so in the role of coordinator for the doctoral education program in languages and linguistics, which spanned a multitude of departments, in 1997-1999 and 2002.

In the early 2000s, Hans Petter Helland, professor of French linguistics, and I collaborated closely to plan and implement the integrated education program Språkprogrammet (The language program).

This and other efforts to join together what belongs together have not met with unmitigated success. The integrated language program was dismantled after less than ten years, and walls between departments where linguistics is done have been built ever higher. Still, the Forum for Theoretical Linguistics, the seminar series descending from professor Fenstad's late 1970s and early 1980s Seminar i lingvistikk, at least made it into 2024.

Over the last twenty years, my closest collaborators have been Atle Grønn, professor of Russian linguistics, and Dag Haug, professor of classical languages and linguistics. Together with Torgrim Solstad, now assistant professor of linguistics at the University of Bielefeld, they initiated and edited a Festschrift for me which appeared in 2006 – see separate entry under Miscellanea.

In 2007, Atle and I – practically single-handedly – organized the 12th Sinn und Bedeutung conference (SuB12) (see separate entry under Miscellanea).

Since 2012, I have had five very gratifying experiences professionally.

- In 2013, as a fellow under the Wigeland Endowment, I was able to spend the fall quarter teaching in the Linguistics Department at the University of Chicago. Chris Kennedy initiated this and made me feel at home in the department and on the lake.

- From 2014 through 2019, I served as a member on the scientific advisory board of the Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (ZAS) in Berlin.

- From 2015 through 2019, I was an adjunct professor (10%) at the Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø, affiliated with the CASTL-FISH group, spending a total of ten weeks there.

- In 2018 and 2019, I spent four weeks as a mentor and guest researcher in the Zukunftskolleg at the University of Constance, where Sven Lauer and Doris Penka were my hosts.

- From fall 2013 to fall 2019, I served on the editorial team of Semantics and Pragmatics, and since fall 2019, Louise McNally and I have been editors in chief of this journal (see separate sidebar item S&P).

I am deeply grateful for all these engagements.

Personal Paths

That is the house I lived in from 1958, when I was two, to 1965, when I was nine, in Malvik municipality just north of Trondheim. Built as a navy convalescent home during German occupation, it was now a boarding school for hearing impaired children where my mother taught and my father was director. We lived at the far end of the house. The pupils came from all over Norway, and they were my playmates.

In an interview with the Trondheim daily Adresseavisen on the occasion of my doctoral defense in 1986, I said that this was what awoke my interest in how we understand each other with language. The ways of expression were widely varied, making communication a demanding and thought-engaging undertaking.

My father and mother came from two of the regions where dative case varieties of Norwegian are spoken: Romsdal and northern Trøndelag. They finished their training at Levanger teachers' college in 1943 and took up posts in single class schools in inner Romsdal. The photo shows my father's class, him, and the goat which had to be admitted to the classroom, or the boy behind it would not enter.

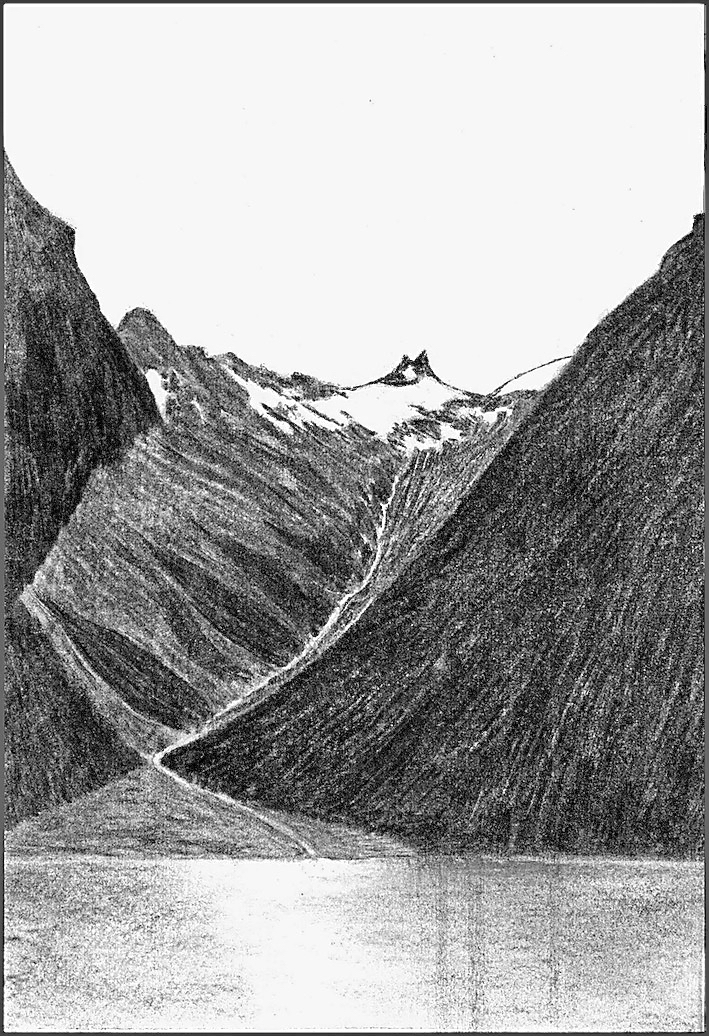

The drawing shows the location of the lone farmstead where the school occupied the living room (the two buildings at the lake Eikesdalsvatnet are abstracted away).

My mother's parents met in Varanger at Norway's extreme northeast end. Her mother was a midwife based in Kiberg, her father, originally from Lofoten, worked as a miner across the fjord. In 1918 they went to North Trøndelag to take over the farm from her parents. My mother had been born in 1917.

My father's parents married in Minneapolis, Minnesota, during World War I. His father had emigrated on the Carmania of the Cunard Line in 1912, his mother, shown in the photo, on the St. Paul of the American Line in 1914. She worked as a maid, he had a succession of jobs, from threshing hand to streetcar conductor. In 1919 they returned to their home village in Romsdal to take over the small farm from his parents.

My father was born in 1921. The small family was planning to re-emigrate to the USA towards the end of the 1920s, but my grandfather was denied entry because of a medical test result. This made it possible for my parents to ever meet.

My maternal grandfather suffered a misfortune on a similar scale: Due to take up study at the Norwegian Agricultural College at Ås, he was travelling by train from Trondheim to Oslo when all his money was stolen. This forced him to abort his education, and he went north to eventually meet my maternal grandmother.

My family moved from Malvik to Oslo in 1965. I was nine. The first years I was a lonely kid, mostly interested in reading. But gradually, I got some friends, through orienteering, through the church, and through high school, the downtown Hartvig Nissens skole, known in later years from the TV series Skam, and I discovered jazz music, particularly Ellingtonia. Playing the piano has given me much pleasure ever since.

In high school I did drama, as did my wife, my daughter, and my daughter-in-law, all at the same school, in intervals of one, thirty-five, and thirty-seven years. Amateur theater remained an important part of my life for some ten years after I graduated in 1974. When my future wife and I met in 1977, I joined the small troupe she was putting together to stage a variety show based on once-popular ballads, Hjerterom tilleie, as guitarist and arranger.

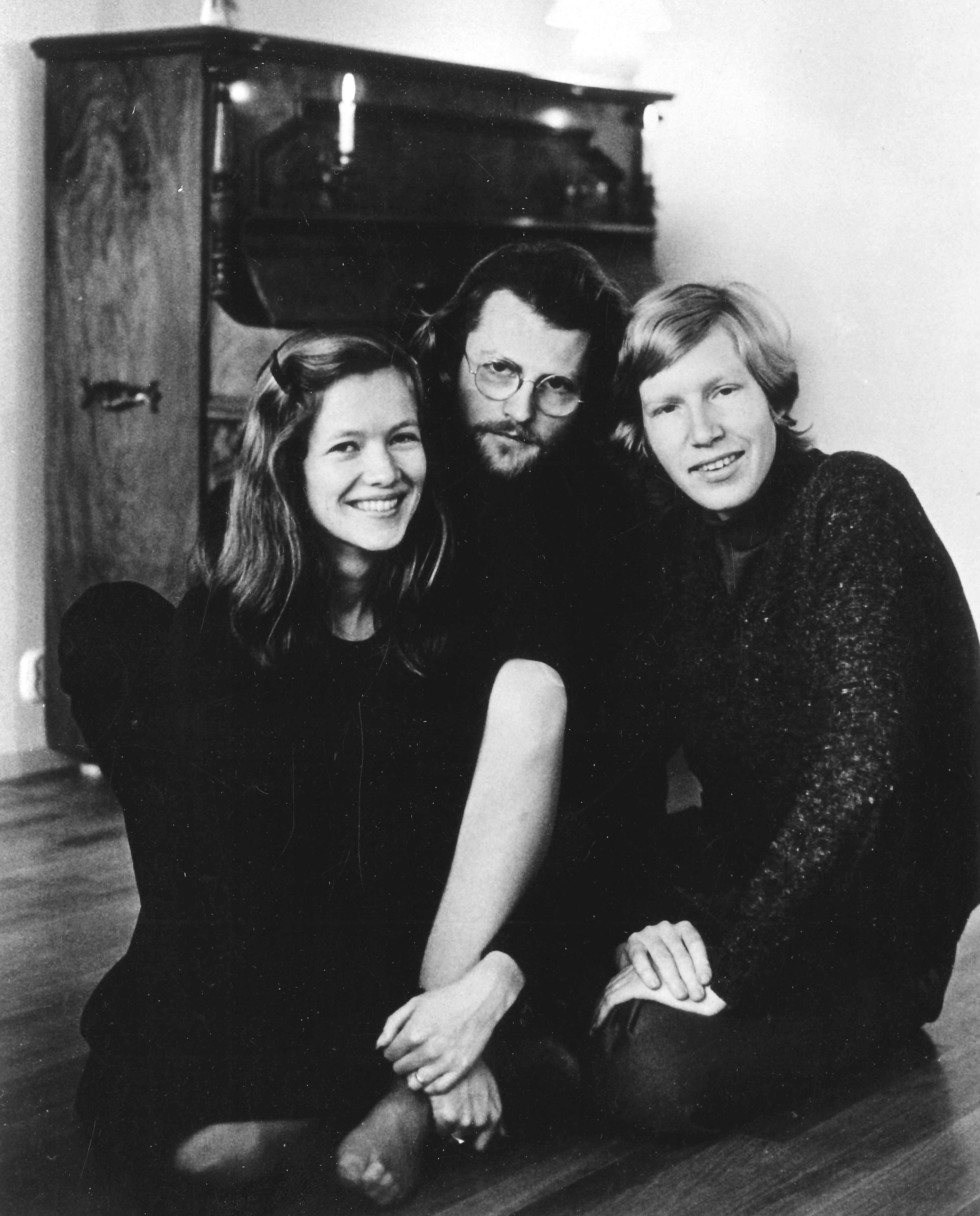

In 1980, staging the self-written variety show Amerikasuiten was a still smaller troupe consisting of my fiancee, Kirsten Ropeid, Torstein Winger and me. The photo shows us in late 1982, when we started performing our self-written and self-composed show Sivil i krig og frykt: En satirisk kabaret om forsvarsvilje, whose theme was the renewed nuclear arms race of the early 1980s. Our show was much in demand, riding a wave of peace activism. Calling ourselves Kujonene then, 'The Cowards', we did some 40 performances across Southern Norway stretching through late 1983.

It is a cliché, not least in Norway, to say of oneself that one treasures nature, but it is none the less true of me. I love hiking in forests and mountains. And while maps are dear to me, I especially like to not know exactly where I am or am heading but go on.

And to row, on lakes or fjords. The drawing shows a scene from a mountain hike, the below photo shows a scene from a boat trip.

For hiking, I am lucky to live where I do, on Oslo's eastern rim. From nearby one can walk on for 25 kilometers to the southeast without seeing a house or a road. The forest is creased with granite hills and ravines shaped and smoothed by glaciers moving south ten thousand years ago. The trees are predominantly pines.

The photo was taken around 1970 with a Voigtländer camera manufactured in the early 1960s. The film was Agfa CT18. A gale was coming up, and my father, my sister and I barely made it to shore.